Derrick Rose scored fewer points in the NBA than Harrison Barnes and averaged fewer per game than Antoine Walker. Like Brandon Roy, another ascending guard whose career was destroyed by injuries, he made only three All-Star teams. He never averaged eight assists or rated as a particularly effective defender. Even at his peak, he was never an especially efficient scorer. Taken in isolation, these are things that would keep most players out of the Hall of Fame.

But Rose won an MVP, and winning an MVP, in basketball, is an automatic ticket to the Hall of Fame. Every MVP in NBA history is in the Hall of Fame except for the nine that played last season: LeBron James, Kevin Durant, Stephen Curry, Russell Westbrook, James Harden, Giannis Antetokounmpo, Nikola Jokic, Joel Embiid and Rose, who retired on Thursday. The first eight would be Hall of Fame locks with or without their trophies. Rose is the outlier here. He generates debate because of the unusual arc his career took. He is the youngest MVP in NBA history. After his third season, he appeared destined to rank among the greatest point guards of all time. He tore his ACL in the opening game of the playoffs the following year and was never the same again.

There aren’t any exact analogues for Rose in the Hall of Fame, but there are approximations. Bob McAdoo stands out. Like Rose, he won an MVP at a very young age (23, in his third season). Like Rose, his prime was relatively brief. He made only four All-Star teams. His individual numbers were better, and he benefitted from winning championships with the Lakers late in his career. He had to wait a bit to get into the Hall of Fame—his induction came in 2000, 10 years after his retirement—but he made it nonetheless. Rose will as well. He might not even have to wait.

This is not, contrary to what the tone of this story may imply, an argument against Rose making the Hall of Fame. Frankly, the Basketball Hall of Fame has committed far more egregious errors. Everyone seems to make it. Mitch Richmond was a scorer who never averaged 26 points per game across a season and played in only 23 playoff games. He made it. Maurice Cheeks was a defender who never won Defensive Player of the Year or came close to averaging 20 points in a season. He made it. Michael Cooper never made an All-Star Team, but made the Hall of Fame.

Rose at his peak was better by a wide margin than any of these players, and there is something to that inherent within the Hall’s very name. It’s the Hall of Fame, and if it is going to keep taking these “Hall of Very Good” candidates like Cheeks and Cooper, it almost has to take the player who very clearly reached the “Fame” threshold even if he did so only briefly. Rose is the reason LeBron James did not win five straight MVPs. That is a level of historical relevance Mitch Richmond never had a chance of achieving. By the standard of Richmond’s induction, Rose has to make it.

But the standard is worth interrogating, because other sports are notoriously less inclusive. There are 14 NFL MVPs not currently in the Pro Football Hall of Fame, not including active players. That number is 57 in baseball, though in fairness, the steroid era plays a big role in some of those potential snubs.

Of course, MVPs are not all created equal. A basketball player has far more power to exert influence over a game or a season’s outcome than a baseball or football player does. Derrick Rose winning an MVP in the NBA says a lot more about what kind of basketball player he was than, say, Shaun Alexander’s NFL MVP says about his own football career. When Alexander won MVP, he touched the ball around 24 times per game.

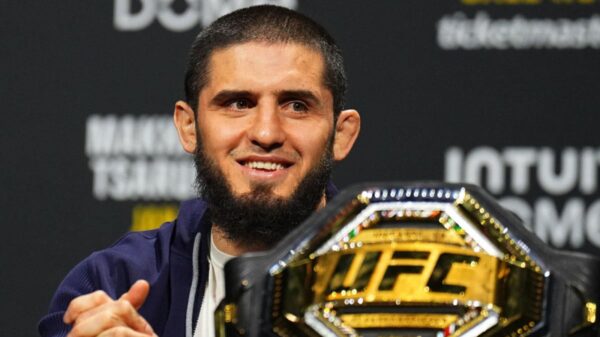

As a point of comparison, Jokic, the reigning MVP and winner of three of the last four, touched the ball over 100 times per game on average. Success in football usually comes by committee. An offensive player can’t succeed without the help of his line. He needs other weapons to draw defensive attention away from him. Baseball is much more of an individual sport, but it’s also an egalitarian one. The MVP doesn’t get to hit more often than the No. 9 hitter. In basketball, the best players can impact as many plays as they want, and while they are certainly influenced by teammates, it is to a far lesser extent than it is in football. In short, winning an MVP in basketball certainly does mean more.

It isn’t just longevity-deprived MVPs making the Basketball Hall of Fame, though. At least then there would seemingly be a unifying standard: players who reach a certain level of excellence, regardless of how long they maintain it, would stand as Hall of Fame-caliber. But we also have to reckon with the Coopers and the Richmonds of the world, the eclectic group of very good players who are eventually and seemingly inevitably enshrined without any sort of overarching theme connecting their careers. That the process is so opaque—done through nomination and committee rather than any sort of public ballot—only makes it harder to find a standard.

Whatever that invisible standard is, Rose has met it. He’s better than a meaningful chunk of the NBA players who have been enshrined, and if the goal of any Hall of Fame is to serve as a museum of its sport’s history, the history of the NBA over the past 15 years can’t be told without Rose’s inclusion. He’ll make the Hall of Fame even if we never quite know what that Hall of Fame is trying to accomplish.

Read the full article here